Anime: It’s About the Hits Stupid

Above: Lady Gaga conquers Japan — love her or hate her, you can’t ignore somebody who has a hit.

I just read yet another blog entry on how illegal fan subtitled shows are killing anime, which I think misses the point. Anime is yet another branch of the entertainment business, and despite how much we fans pride ourselves on how different we are the cruel fact is that the only thing that really matters at the end of the day is that only the hits count. Now some economists will all harp about “the long tail” effect, but the harsh reality is that show business is a popularity contest (just like high school). And even in an industry that has been worse hit by piracy like the music industry you still have the likes of a Lady Gaga who is pulling in the moolah — and is thus a success.

Now as hardcore fans we have a tendency to slag the shows that become the most popular — yet to be honest about it those shows are the lifeblood of getting news fans interested in the genre. In fact if you look at the history of anime in the United States you’ll see that it’s in fact a series of hit series and feature films that attract a new audience.

The first anime fans that I ever met fell in love with the genre thanks to shows like AstroBoy and Speed Racer — and of course growing up with Godzilla movies encouraged that curiosity in what was going on in Japan. These early fans would actually collect 16mm film prints of their favorite shows, so think about that the next time you come across an overpriced DVD box set. These early fans welcomed successive waves of the curious who came in from the cold thanks to shows like Star Blazers, Robotech and the film Akira.

Above: Part of what powered so many VHS and later DVD anime sales were casual fans who loved shows on Toonami who wanted to try some other anime shows.

However it’s in the late 90s that anime started to really bloom — and that wasn’t because of VHS tape sales to those hardcore fans. The reality is that anime boomed in the 90s because of cable television. Honestly if it weren’t for the liked of the Cartoon Network there might be an anime fandom in the United States, but it wouldn’t be any where near the scale of what you see today. The shows that introduced a generation to anime were series like Sailor Moon, Pokémon, Dragonball, Cowboy Bebop, Naruto and Bleach.

Many of these shows were so good, so different than anything you’d see in America that it would cause a casual fans to go on the net and find out more about anime. And I think the key here is that each of those shows offered something unique that American audiences hadn’t seen before. Honestly if the Japanese has kept making the type of science fiction shows that I loved in my youth anime wouldn’t haven’t attracted the large audience that it has in America.

Above: Serious anime fans of the 80s looked down on upon magical girl shows like Minky Momo — little did we realize that Sailor Moon would own anime fandom just a few years later.

And you have to apply that mindset to the anime series that have come out in the last few years. For example if you look at a show like Soul Eater it really owes a great deal to Death Note and Bleach. Now it’s a well animated series that is well crafted — however it’s not going to bring in any new fans. It will keep the fans who first fell in love with Bleach happy, but it isn’t going to open any doors.

Now if you’re a producer in Japan and the market is tight you don’t want to take any chances. Anime is still quite expensive to produce and if you try something new you risk throwing money away. The result? Yet another show about a harem of robot maids that we’ve already seen before. The producer makes his money back, a small hardcore of fans like the show and buy expensive figurines of these sexy maid robots, but what doesn’t happen is that a ten year old kid in Iowa doesn’t stumble across something that gets them excited enough to tailor a cosplay outfit.

Is this the death of anime? No! But as usual those who don’t embrace change in the industry will find themselves on the way out. I know this from my own personal experience having watched it first hand in the early 90s. My mentor was Claude S. Hill the man responsible for the show Star Blazers and he was above all else a broadcast television guy. He made his money from syndicated shows that would air on independent television stations, and even have a show on just a few of those stations would give you a nice stream of income.

Above: There are only 308 days left to save anime — hurry Starforce!

Star Blazers was already slightly dated at this point, but a good proof of concept from that era would be shows like Robotech or Transformers. These shows were a big business and that money didn’t come from VHS tapes — a notion that would have been laughable in the late 80s. These shows made their money from two sources: Advertisements when the shows aired and in the sales of countless toys that kids would ask their parents to buy them.

The selling point of anime to these entrepreneurs was that it was cheap. Yes read that word again — cheap! Creating an American show cost money to produce, so licensing an anime title was inexpensive and dubbing it was a small cost when put next to starting from a storyboarding phase. And better yet the merchandising plan was even more simple: Just get the toys from Japan, bring them over here and put them into new boxes. And that’s why when put next creating a show like He-Man that anime was a good business proposition.

Above: For American producers putting a show on the air like Robotech was a smart move because the quality of animation was better than a He-Man yet it was very cheap to license and dub.

Now getting back to my mentor Claude Hill: In the early 90s he just couldn’t understand what another anime entrepreneur was doing. The man in question was John O’Donnell of Central Park Media. Mr. Hill just couldn’t understand what the hell John was doing! O’Donnell came from the ranks of Sony where he made his reputation selling VHS tapes in the 80s. The focus was on titles that would appeal to a small niche audience. So for example a Duran Duran concert tape would cost very little to produce, but would make a bit of money back for very little expense and a bit of patience.

But to Mr. Hill this business seemed like a total waste of time: Why spend all of that effort to even get a show if it wasn’t on air? What we didn’t see at the time was that through VHS tapes John O’Donnell was embracing what we in the tech business call a disruptive technology. I’ve got to tell you that those VHS tapes were terrible — they were often subtitled and the ones that had dubbing were horribly amateurish. John fought pitched battles to even get video rental shops to understand that this anime stuff didn’t quite belong in the kids section of the shop.

Now something you need to understand: What Claude Hill was doing came from the kids section of broadcast television. So when O’Donnell would bring over R rated and even X rated titles that represented a real clash of cultures. In fact from my own experience having worked on kids television I can tell you that the golden rule is that working on anything even mildly adult can be a death sentence. So as you can see in terms of a vision of what anime was to Americans you’re looking at a real dividing line.

Above: Project Ako could never get onto broadcast television in the late 80s, yet on VHS it kept many anime fans interested in the genre. Looking back at it what made the show so different (i.e. the girls in their sailor suits) seems to dominate much of what we think of what anime is today.

As time went on I came to see that Hill’s company was slowly fading. He had produced the third series of Star Blazers, but while it did alright it wasn’t a huge hit. The lack of funds prevented him from doing more development. However O’Donnell was just at the beginning of a mini-boom of sorts. As more and more video stores popped up and became more sophisticated they started to carry anime titles. Better yet other shops like record stores and book stores also ventured into having VHS sections.

The result? Suddenly selling VHS tapes had become the anime industry by the early 90s. Yes some shows would make it onto cable networks, but that wasn’t where the real money was because none of those shows produced real hits at that point. That industry of selling VHS tapes and later DVD box sets has now been with us for twenty years — but I think it’s now in an end game.

Above: In the 80s and 90s laser discs appealed to a small niche audience of collectors — my bet is that with Blu-ray we’ll be getting back to that while normal folks will consume digital.

Right now we are in a disruptive period where the economic models are changing again. Ironically with video streaming I can see things returning to a previous model where advertising and selling toys pays the bills. Of course history rhymes more than repeats itself as this new model won’t be exactly like the old model. New services like Cruchyroll may make their money from subscriptions in addition to advertising, and the Japanese may sell their toys directly.

So when I read about some voice acting company complaining that “anime is dead” I’ve got to laugh at them. It’s not that anime is dead, it’s just that it and the wider entertainment marketplace is changing. This first wave of shows that you’ll see on Cruchyroll will be subtitled when they’re being streamed live from Japan. But my bet is that over time one of those shows will become a hit, and you’ll see Cruchyroll hiring voice actors.

As for anime itself my bet is that as soon as everyone is convinced that it’s turned into a small niche market that isn’t worth looking at that some show that only a few hardcore fans know about will go on to become a blockbuster hit that brings in the next generation of fans. You might even see a show that appears first on a streaming site make the jump to a cable network after it has proven its popularity. Or maybe a best selling videogame or light novel might open the door: The point is that you never know and can’t predict.

In these situations I’m often reminded of that famous quote about a new musical act that wouldn’t make it because “guitar bands are on the way out”. The experts that decided this were the executives at Decca records who turned down the Beatles.

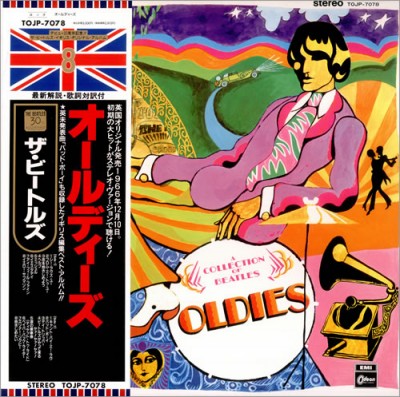

Above: A Japanese Beatles record.